Archive

Categories

- Education (19)

- More Personal Posts (18)

- Opinion Pieces (16)

- Relection and Learning (16)

- Research (6)

- Strategies (4)

- Uncategorized (4)

Follow me on Twitter

My Tweets

Giving options to students

An element of my PhD research is Self-Regulated Learning. I believe that if we want students to mature into well-rounded adults, we should give them opportunities to make decisions around their learning. I believe in scaffolding questioning and activities to help students develop metacognitive awareness, as well as an understanding of their own learning preferences, what works best for them, and where their strengths and weaknesses as learners lay.

One of the ways I’ve been doing this lately is by giving students options regarding how they develop skills in a mathematical area. This does create some extra work for me, but for me it is worth it to help students create ownership in their learning. An example of some options I might give are:

- Complete an exercise from the textbook: it might not be trendy, but many students actually like working from a textbook

- Complete an activity from their online learning program: we use IXL at my school, I have also used HOTmaths and MathsOnline previously at other schools, and many other similar programs exist. In particular, some of my boys tend to prefer working with their laptops.

- Use an online game: again lots of sites out there, can make ‘drill and repetition’ style practice fun)

- Do a worksheet.

I also supply tactile materials for students that have a preference to use these. In my room I keep matchsticks, centicubes, counters, 3D shapes, and die.

The options I give are dependent on the year group, the material that we are covering, and my plans for the lesson. I’m more likely to give an ‘options’ lesson after lunch – unless I have something else planned (e.g. today we workout out how many post it notes it would take to cover the class room, how much it would cost, and how long it would take).

The main issue I’ve found with this approach is ensuring that all students are covering the same material and the same or similar types of questions. Additionally, there are obvious concerns with printing out and photocopying worksheets when students may not be completing them – this requires some guess work.

Have you played around with giving students options for how they complete their work? What challenges or successes have you had with it?

Posted in Strategies

Leave a comment

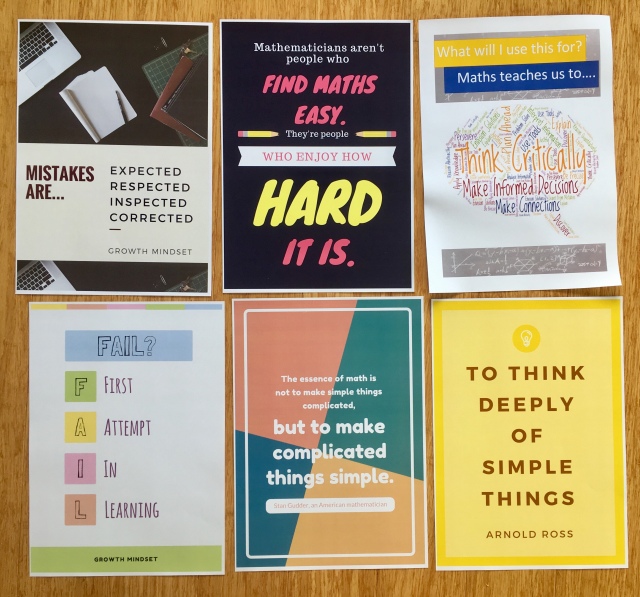

Using Canva to create posters

Over the Christmas holidays I was feeling highly motivated to do something ‘school related’ but also just wanted to something that was more along the lines of busy work, rather than, say, planning my lessons for term one. I was scrolling through Pinterest, feeling very inspired by how aesthetic some teacher’s rooms were and realised that I too could have a Pinterest inspired classroom. Maybe.

In particular I loved some of the posters I was seeing, particularly ones focusing on growth mindset. I wasn’t so keen to pay $10-$15 per poster though (#renovationlife). So I turned to Canva (#notsponsored). Canva is a design website that allows you create a range of stunning designs based on templates, or you can create your own from scratch. There’s also an app available for iPhone, iPad, and Android. Templates available on Canva include invitations, flyers, photo collages, posters, infographics, letters, lesson plans, newsletters, and more.

My process for creating my posters is simple:

- Choose content for the poster – this is often inspired from Pinterest or the unit we are covering in class.

- Choose an appropriate template using the thousands available

- Create my design

- Save a copy of my design as a PDF (see below).

- Upload my PDF to Officeworks print and copy

- I select A3 size, cardboard, high quality. For a grand cost of $1.78 per poster. My posters are usually available for collection in store in 2-3 days. I love that I can upload from my laptop and then collect in store at a time that’s convenient for me!

I’ve found that this process is pretty quick and simple, once you get the hang of it. There’s tonnes of tutorial videos on YouTube if you need some extra guidance.

Canva is a great way to create personalised posters for your classroom, at a great price. Have you used any design apps in your classroom to create content? What have you found works best?

Posted in Strategies

Tagged advice, beginning teachers, blogging, Canva, math education, reflections, school, teacher, teaching, wordpress

Leave a comment

Flipped learning: it’s not all “WooTube”

Over the Easter long weekend a spate of articles about Flipped Learning were published. Eddie Woo’s profile as the “Kim Kardashian of the maths teaching world” (Adam Spencer), was further enforced, with appearances in articles by the Sydney Morning Herald and on The Project. Whilst I enjoy positive articles about teaching (it makes a change from lamentations about the state of education and need for “quality” teachers in Australia), some of the points in the articles were a little misguided.

Flipped learning is hardly a new approach to teaching: Khan Academy was founded ten years ago in 2008. The origins of flipped learning are attributed to academics at the University of Miami in the year 2000. As devices and wifi have become more widespread and accessible, however, it has followed that implementation of flipped approaches to learning have become more widespread.

Not Eddie Woo

Flipped learning isn’t just about Eddie Woo. Eddie Woo is a fantastic (top 10 in the world teacher), but the fact that he publishes his lessons to YouTube (WooTube) doesn’t mean that his lessons are flipped. On viewing any of Eddie’s videos it is apparent that Eddie typically using a traditional, direct instruction, ‘chalk and talk’ approach. What distinguishes Eddie is his capacity to incorporate effective communication, enthusiasm, and productive relationships with students to result in engaged, high quality, mathematics learning. Fantastic? Yes. Flipped learning? Not so much.

Flipped learning has many great applications beyond communicating content through videos. Some ways that I’ve enjoyed using flipped learning include:

- Using screencasts to explain activities or assessment tasks. In the following

Creating screencasts on a macbook (post to come)

example I’ve used a screencast to explain an activity to my year 10 religion class (see here). I basically just talk through the assessment task/activity (using a word doc or google slides) and then provide the link to students using google classroom (the platform my school uses). Students can then access the screencast for additional instruction regarding the task/activity, which can be beneficial in promoting independent learning.

- In whole-cohort assessment tasks, supplying the one video explanation to all students ensures consistency between classes.

- The use of screencasts can also be an effective way of communicating with students when the teacher is away, particularly as these can be uploaded remotely and accessed as students progress through a unit.

- A struggle with mathematics homework is that it’s often too easy (to ensure that students can do it) or too hard (resulting in a frustrating experience for students and parents). My preference is often to set note-writing as homework so that in class time can be spent working through examples and problems: the sort of work that students typically need help with. I’ve found this approach successful for all high school grades, but it can be problematic if students don’t have time to complete work at home (due to work, sport, and other activities).

- Setting reading as homework, that might involve application of content (e.g. this SMH article about compound interest). We can then spend class time discussing and applying the concepts described in the article.

A concern in flipped learning is equity: it cannot be assume that all students have access to the internet or devices at home and not all schools have 1:1 devices. Setting entirely web or device based flipped activities further disadvantages students who may already be experiencing hardship. An advantage of some of the above listed activities is that they don’t require access to internet or devices: articles can be printed prior to class or students can be assigned notes from content contained in their textbook.

I’m interested to hear from other educators: what approaches have you used in flipped learning and what steps can you take to ensure equity amongst students when flipping your classroom?

Posted in Strategies

Tagged Eddie Woo, flip classrooms, flipped learning, math education, maths teaching, reflections, school, teacher, teacher quality, teaching, youtube

Leave a comment

Index cards: a not-so-novel approach

So the title for this post is clearly a little tongue in cheek – Carl Linnaeus invented the Index Card in the 1760s, and they’ve had a wide number of applications since then, including to education. On twitter tonight, though, a post from @EduTweetOz got me thinking about how I use index cards in the classroom, and the fact that for some beginning (or established) teachers, their use in the classroom may be a little novel.

I always keep a stash of index cards in my teacher pencil case and I find them a handy tool in the classroom. Some of my favourite ways of using them are:

- “My Favourite No” – I frame this as an activity at the start of a lesson, where I’ll put a problem on the board which is either novel (testing students ability to apply what has been taught in previous lessons), or is a recap of what has been learned previously. Example: “Question: find the surface area of a triangular prism (year 10 maths). Students complete the problem on the index card, I collect the cards, and flip through, looking for common sources of error. I then copy the problem to the board exactly as the student has written their solution. As a class we go through the student’s problem, discussing the sources of error and affirming what has been done “well” in their attempt at solving the problem.

- As an exit ticket to review the content that has been covered that lesson. It might be a problem relating to the maths work covered that day (or earlier in the week), to write an introductory paragraph on a content covered that day in a humanities subject, or to write a sentence using new vocabulary learnt in a language subject

- Asking students to write their own problem, relating to what has been covered that day, and then get them to solve it. Extension: ask students to identify where the ‘sticking points’ might be for other students.

- Reflection. It’s no secret I’m a big fan of integrating reflection/metacognition into my classroom (I’m writing a PhD on it), and I love to tie together a lesson with some reflection questions. Some of my favourites are:

- What was the most important thing you learnt today?

- What was the key idea of today’s lesson?

- What are you finding most tricky at the moment?

- What are you finding is helping you learn at the moment?

- What questions do you still have for me?

- What is stopping you from reaching your potential in (maths) at the moment?

- What is a success you’ve had lately?

- What are some of the key terms from this week’s lesson?

- What is an important formula or rule you have learnt lately?

I’ve enjoyed spontaneously pumping out this post this evening; I have been thinking recently about getting back into blogging and sharing some of my thoughts. My PhD is slowly edging towards completion – I’m hoping to have it submitted mid-year.

I would love to hear your thoughts about using index cards or similar materials in the classroom – how do you love to use them and what do you find effective? I have heard of other teachers using post-it-notes effectively to enhance their practice and communication with students.

Until next time (which hopefully won’t be another four years away),

Madeline.

Posted in Relection and Learning, Strategies

Tagged advice, education, flipped learning, learning, math education, mathematics, reflections, school, teacher, teacher quality, teaching, test, testing

2 Comments

Update on Matthitude

I’m at somewhat of a critical point in my research. Data collection was completed around a month ago and now I’m into the hard number (or in my case interview and observation) crunching phase. Whilst I am maintaining activity on twitter, my time will be best spent at this stage focusing on writing and preparing for upgrade to PhD.

For this reason I’ve decided to reduce the frequency of blogging to every 2-3 weeks until I submit for upgrade. I’m working hard to complete some analysis for my supervisors before heading out to Armidale next week. Then it’ll be a few hard weeks of work before I submit some time in June (all things going to plan!).

In the mean time you can follow my activity on twitter @Madeline_Bev

ATAR: A Terribly Awful Result?

The article Time to put the ATAR to the test by Adam Spencer raises a number of important questions regarding the future of the ATAR in determining year twelve students’ admission to university.

The ATAR is a rank, ranging from 30.00 to 99.95 which is the raison d’être for many senior school students. This rank provides the basis on which they will judge all past, present and future success. With over 250,000 people applying for places in hundred of courses in the 39 universities in Australia each year, it makes sense to have a tangible yardstick by which to base admission. There exists a number of flaws to this system, however, leading many educators to question the future of the ATAR.

In his article, Spencer highlights that although the ATAR is a reasonable determinant of ‘group aptitude,’(i.e. a group of students who scored in ATAR the 90s will probably outperform at university a group of students who scored ATARs in the 70s) it is less meaningful for comparing students on an individual basis.

Recently, concerns have been raised over students purposely selecting subjects in the hope of maximising their ATAR whilst disregarding courses that will be useful in their intended university course. It is much easier to achieve a high mark in General Mathematics than Mathematics Extension Two, for example. The result of this is that students are ill-prepared for university study. The Victoria Curriculum Assessment Authority, in the Strengthening Senior Pathways Report, emphasised these concerns regarding subject-selection.

“In some instances, decisions about a program of study at the senior secondary level are being compromised by an unhealthy and increasingly unnecessary focus on maximising the ATAR… sometimes at the expense of either enrolling in a wider range of different learning opportunities or pursuing a specialist area of interest and/or excellence.”

ATARs are yet another means by which the cycle of disadvantage can be perpetuated. Students from low socio-economic backgrounds face a range of social and economic disadvantages, such as low quality living environments, limited access to technology, underemployment and under-education of family members, poor health and discrimination.

Whilst ACER suggests secondary school curriculum are not the source of SES inequality in tertiary entrance performance, it is clear there are significant inequities with respect to ATARs and students’socioeconomic status. A study from the Centre for the Study of Higher Education explains that:

“…high SES students who were achieving similar grades to low SES students in Year 9 went on to achieve ENTERs [ATARs] around 10 points higher three years later.”

Which serves to add to existing concerns highlighted in a University of Melbourne report prepared for Universities Australia that there is

“Persistent under-representation of low SES people and Indigenous people in Australian universities”

These are real concerns for all Australians. We cannot pride ourselves on being a nation of equity with an ethos of a ‘fair go’for all where persistent disadvantage is the norm. A country where students in the highest socioeconomic group are the equivalent of two and a half years in front academically of students from the lowest socioeconomic group. A country where students from the lowest SES quartile are eight times more likely than the top quartile to have failed to meet the most basic levels of proficiency in international testing.

ATARs present skewed ‘evidence’of school quality, with schools under ever-increasing pressure to maximise students’scores above all else. Students from Independent schools are 2.7 times more likely to be admitted to university, as Claire Brown suggests at The Conversation, perhaps post codes would be equally useful basis for university entry. The assumption that ATAR scores predict school quality is blatantly wrong. The fact that over 70% of students at James Ruse scored ATARs over 90 is indicative of the type of student enrolled at the college, not the calibre of school leadership or the quality of its teachers (though these factors obviously play a role in Ruse’s continued performance).

Further, arudimentary understanding of the ATAR system leads students to believe that they are in a competition with their classmates for ranks, which encourages negative learning habits and disincentivises collaboration and sharing between peers. Further, the ATAR encourages students to think of themselves solely as a number, and place their worth in that number. This mindset is incredibly dangerous in a demographic already at risk for a vast number of mental health issues and facing enormous pressures from themselves, their peer group, and their parents to achieve highly.

The assumption that ATAR reflects course quality is inaccurate. ATAR is a supply and demand model. A high ATAR is not indicative of course quality: it simply indicates that a large number of students wish to enroll in that particular course. Students feel pressured not to ‘waste’their ATAR points and should enroll in the course with the highest cut-off possible. Hence the (surprisingly?) common lament of “I’m doing law/medicine/dentistry because I got the ATAR.”When I was in year twelve I faced similar pressures. When discussing my intentions to study teaching all-too-often I would hear “but you’re going to get high 90s…what a waste!”

Increasing numbers of students do not even utilise an ATAR as the basis for admission to university. Recent figures suggest half of new students are mature aged and 2/3 of uni students do not have an ATAR. Students are instead using alternate forms of prior learning for the basis of university entry. This includes vocational qualifications, work and life skills, and alternative aptitude and admission tests. Entry to undergraduate medical courses often requires an interview and UMAT examination, whilst entry to performing and creative arts programmes generally require auditions or examinations of students’ portfolios. There exists scope, however, to expand such means of entry to a wider array of courses.

Raising ATAR cut offs has been suggested as a means for improving the ‘quality’ of teaching qualifications and hence generating more quality teachers: feeding into societal (mis)conceptions that a higher ATAR is indicative of a more exclusive and hence more prestigious and desirable course.

Criticisms that admitting students with lower ATARs will ‘dumb down’ the quality of education are inaccurate and misleading. There is a lack of compelling evidence to suggest that students’ who achieve the highest ATARs are the best students, or that the highest quality programs at universities are the ones with the highest entrance scores. Andrew Norton, of the Grattan Institute Higher Education program shows a weak relationship between ATAR and average marks. However, there is a strong relationship between a higher ATAR and completion of a degree. The latter may be influenced by students from lower SES backgrounds being forced to work higher hours in part-time jobs in order to support themselves at university, rather than having the privilege of parents covering their living expenses. In these cases, it is pertinent to reflect that ATARs do not measure aptitude for university study, which is very different from the school environment, no do they predict the ability of a student to achieve with or without effective teaching and support. It is merely a rank.

I don’t oppose ‘measuring’ things, and as a mathematician with a penchant towards quantitative data, it would be foolish of me to cast aside another avenue of data to explore. However, the time has come to acknowledge the shortcomings of the ATAR as a basis for admitting students to university and to look to developing more inclusive, balanced approaches of scoring that encompass these difficulties and better facilitate students’ access to university education.

Posted in Education, Opinion Pieces

Tagged Adam Spencer, Andrew Norton, ATAR, Board of Studies, Claire Brown, disadvantage, education, Grattan Institute, higher education, HSC, NSW, school-leavers, ses, socioeconomic status, university, university entrance, University of Melbournce, year twelve

Leave a comment

NAPLAN: The Assessment that needs Assessing

NAPLAN has been back in the headlines again recently (although, when is it every really OUT of the headlines?): this time in response to a senate inquiry investigating concerns NAPLAN is damaging to student and teacher wellbeing and creating a culture of ‘teaching to the test.’ After six years of NAPLAN testing, at a cost to ACARA of $7 to $7.5 million per year, it is time to put NAPLAN to the test, so to speak.

Greens Senator Penny Wright, in handing down a Senate inquiry into NAPLAN testing, has recommended significant changes need to be made to both the tests and MySchool website.

“The committee heard a huge amount of evidence that the MySchool site has introduced a competitive element which is damaging student and teacher wellbeing and resulting in a whole lot of ‘teaching to the test” Senator Wright said.

“As a committee we came to the view it’s time the ranking and comparative functions for individual schools on the MySchool site were removed. The committee also thinks that NAPLAN needs some improvement as a diagnostic test – it’s just not as helping teachers and parents support students as well as it should.”

In election campaign-mode last year, Education Minister Christopher Pyne suggested the Coalition would consider banning the publication of NAPLAN test data over concerns it was ‘skewing the way people teach.’

In March of this year, however, Minister Pyne substantially softened his standpoint:

”The government committed to review NAPLAN and the My School website to ensure it is meeting the needs of our students.” This statement was a rather dismal indicator for any significant change occurring.

Standardised testing is not new in Australia: state-wide testing of cohorts has taken place since the 1980s. NAPLAN was first introduced in 2008 to replace the Basic Skills Test, or BSC, which varied from state to state. One of NAPLANs aims was to provide nationally comparable data on individual student performance in literacy and numeracy. NAPLAN tests are conducted in May each year, and students participate in tests in years 3, 5, 7, and 9.

I would like to make it quite clear: I am not against standardised testing. The data provided by NAPLAN testing can be useful for both parents and schools alike. Each student receives an individual report which provides parents and teachers with feedback on the knowledge and skills they have demonstrated on their test. This data can be compared to other students in their grade across the country. This element of national comparison means that the data is useful even if students move interstate. Schools can use NAPLAN data to compare incoming students against an existing cohort, and it is common practice for many high schools to request NAPLAN data for students enrolling in year seven. This data is often used alongside other information (such as reports or general ability testing) to place students in streamed classes.

Schools can use data to track trends in areas of student strength and weakness between and across year levels. Teaching can then be structured to ensure these areas are targeted to improve student outcomes. NAPLAN can function to provide a snapshot of how a cohort is functioning as a whole, and facilitate comparisons between year groups..

In reality, however, as a teacher I do not typically use NAPLAN data to inform my practice. Tests are sat in May, yet results are not received by schools until mid-September: leaving only term four to work with students. Rather than expensive and time-consuming NAPLAN tests, in-class assessments and day-to-day monitoring of student learning and understanding is far more useful in informing my practice. As a diagnostic test, NAPLAN leaves much to be desired.

NAPLAN testing can be disruptive to school routine, and with the focus on publishing test data, and the high profile of NAPLAN testing in the media, there is increasing pressure for students to perform well. It is not unusual for heads of department to request teachers spend some time in the weeks preceding the test ‘familiarising’ students with the style of questioning. When teachers ‘teach to the test’ pedagogical practices emphasise rote learning, memorisation, and drills. Testing can motivate performance as students strive to achieve better academic outcomes, particularly when it is not tied to their grade, as in the case of NAPLAN. However, standardised testing can also increase anxiety, promote challenge-avoidance behaviour, and increase levels of self-doubt. Are we willing to sacrifice students’ psychological well-being for the sake of publishing test data?

You may accuse me of scaremongering: naysayers may protest that NAPLAN is not high stakes, but my argument is not hyperbolic. With the level of exposure of NAPLAN in the media, the constant level of scrutiny teachers are held under by politicians, media, and the general public, this supposedly ‘low stakes’ test seems to becoming exponentially bigger each year.

Parents, however, appear to be more fond of NAPLAN testing than teachers themselves. A report by the Whitlam Institute at the University of Western Sydney found 56 per cent of parents were in favour of NAPLAN testing, with around 70 per cent finding the tests useful for providing objective and comparable data. By contrast, just 20 per cent of teachers reported positive feelings about NAPLAN testing (it would be interesting to know how many of the parents that disagreed with testing were teachers).

Why? It is not because teachers are averse to scrutiny (goodness knows we receive enough of it from the media). It is because publishing of NAPLAN data via the MySchool website transforms a supposedly ‘low stakes’ assessment into a ‘high-stakes’, highly-publicised extravaganza. Whenever data is published there is the opportunity for it to be misused and misinterpreted. Publishing of data inevitably leads to production of league tables and uninformed, uneducated comparisons being made between schools and states. It is ridiculous to compare the ACT with the Northern Territory: the two cohorts are entirely different, yet as soon as NAPLAN data is released those types of comparisons are inevitable.

Adjunct Professor James Athanasou encapsulates the issue with NAPLAN as it stands currently

“NAPLAN is not there to swell parents’ egos or to publicly humiliate schools or teachers. The problem is not the test’s assessment, but how it is used.”

Am I proposing an end to standardised testing? No. I do, however, maintain my strong opposition to publishing of NAPLAN data via the MySchool website. Increasing emphasis on ‘measuring’ students and production of transparent data serves simply to focus students (and teachers, and parents) on being performance or achievement focused. The consequence is that that students are no longer learning for mastery and understanding, are less adaptive learners, eschew challenging tasks, and have a greater tendency to blame failure on personal inadequacy (see my post on mastery vs performance learning here.

Ceasing wide-scale publication of test data would be a step in the right direction towards more appropriate use of NAPLAN testing. As long as the MySchool website is in operation NAPLAN will continue to appear to be a high-stakes test. If we want students to be focused on deep learning, on being engaged, challenged-seeking problems solvers, continuing to emphasise NAPLAN is NOT the way to go about it. NAPLAN should function as it was intended: a diagnostic tool that serves to provide information to schools and parents. Not a measuring stick for the production of league tables and a culture of teaching to the test.

Read more

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-03-27/senate-committee-recommends-naplan-overhaul/5349644

http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2014/03/27/changes-naplan-needed-help-disadvantaged-students-senators

https://matthitude.wordpress.com/2013/09/28/pyne-a-pain-for-education-in-australia/

Posted in Uncategorized

Tagged assessment, AusPol, Australia, Christopher Pyne, curriculum, education, high school, learning, mathematics, maths education, NAPLAN, Penny Wright, primary school, standardised testing, teaching, test, testing

2 Comments

But WHY Are You Teaching Maths Ms?

I can hardly believe it: data collection is complete. It feels like only yesterday I was submitting (and resubmitting… and resubmitting…) my ethics application and now it’s all over! Eight interviews have been conducted and transcribed, numerous lessons have been observed, and a class of students have been surveyed and re-surveyed. In the coming weeks I will reflect a little more on the data collection process as I work through the long, iterative process of trying to make sense of my data.The focus of this post, however, is what I enjoy about teaching mathematics.

During my second interviews I asked each of the students what they enjoyed about learning mathematics. I was surprised at the responses I received. One student highlighted what she loved most about mathematics was that success is not due to talent but hard work, and that if you work hard you can do well. Another student enjoyed the way that different aspects of mathematics interact and ‘fit together’ to create an intertwined body of knowledge. A third student simply stated he liked mathematics because he understood it.

My last interview, however, was a little different. I conducted it with a softly spoken and introspective girl. Let’s call her Maggie. Maggie shared with me that she loved that in mathematics you have to learn how to do things, rather than learning ‘things’ as she did in other subjects. Maggie and I then proceeded into an interesting discussion on the nature of teaching concepts versus content.

Maggie voiced exactly why I love to teach mathematics. I’ve had a number of students ask me recently why I became a mathematics teacher. Some of them, knowing that I’m a runner, are confused as to why I don’t teach PE. Others, when they learn I’ve played piano since a young age, question why I don’t teach music. Others still, given that I can spell more than a few words and my vocabulary has progressed past a primary school level, think I should be teaching English. When classroom discussions tend towards the (in particular human) sciences students as why I don’t teach science.

It’s true. I could have probably taught most of those subjects. But they have never held the same magnetism as does maths teaching.

- I love maths teaching because I am teaching concepts, not content. I enjoy the process of helping students understand how to attack problems and think creatively.

- I enjoy that in mathematics there is a defined end target: ‘solve for x,’ but the manner in which you get there is up to you.

- I love that in mathematics you don’t understand everything straight away, and that’s ok. I want to struggle. I want to push myself to understand. I particularly enjoyed this aspect of mathematics when I was studying Extension Two in year twelve: all of a sudden I had to really work in order to be successful. I couldn’t rest on my laurels or natural intelligence.

- I love that teaching mathematics is about teaching persistence.

- I like the ‘toolbox’ approach in mathematics: determining how to apply previously acquired knowledge and skills to novel situations.

- I love the little tricks and cool maths facts. The unique elegance and beauty.

- I love that mathematics is about communicating and problem solving: it’s about how I can coordinate my ideas and string them together in a compelling enough way to convince you that I’m right.

- I LOVE the immense feeling of satisfaction of writing those three perfect letters Q.E.D. (quod erat demonstrandum) at the end of a proof: you know that you’re irrefutably right.

- I love teaching mathematics for that moment when students’ eyes light up and they GET IT: truly this is the most satisfying part of my job.

There is just so much to love about maths. Sure, we might be the butt of many, many, (many) jokes, but I couldn’t imagine teaching any other subject.

Finally, a shoutout to all my maths teachers for contributing to the mathematics teacher I am today: Mrs DeMaria, Ms Daley, and Ms Flood.

Posted in More Personal Posts, Research

Tagged curriculum, education, interview, learning, math, math education, mathematics, mathematics teaching, maths teaching, pedagogy, PhD, research

Leave a comment

Did I Pick the Wrong Topic? (and How to Eat an Elephant) Lamentations of a Research Student.

I must confess, sometimes I stare blankly at my blog wondering what on earth I’m going to write about this week. I set the aim of writing 500 words a week, every week, (well… most weeks) this year, and I hate to not achieve a goal. Particularly when it’s nothing but laziness, lack of vision, or failure to time-manage properly that is stopping me from achieving said goal. This week was another of those weeks where it just felt a little challenging to devise an “interesting” topic that people might actually want to read about. So I let my mind wander over my research from the past week and a bit, searching for some gem of information I uncovered. Then I remembered this. That sinking feeling that I’m sure every research student feels at some (or, realistically more than one) point: did I pick the wrong topic?

Don’t get me mistaken. I love my topic. I like that it’s based in educational psychology, and that whilst I’m investigating a topic specific to mathematics education, a number of the concepts I’m researching are applicable across not only Key Learning Areas, but to other domains such as sport and business. As someone who grew up with a keen interest in medicine and health, (and studied health at university) selecting a topic that delves into this area is a good fit for me.

This study aligns well with my own beliefs and interests. My fascination with goals, attitudes, motivation, beliefs, and reflection is long-reaching. I’m a very self-reflective, introspective individual. My topic was literally borne out of me examining my consideration of what made me a successful learner against a body of research. I think it’s an interesting way to commence research as it is deeply connected and relevant to the primary researcher. The key is ensuring it is generalisable and relevant to other individuals.

My moment of self-doubt the other day was not based on a dislike of my topic. Rather it was a ‘this topic is huge’ and ‘maybe I should’ve picked something smaller.’ It’s true. There are more straight-forward topics in mathematics education. I could have selected purely quantitative data collection instruments. I could have tested whether daily times tables improved students’ test results (or a similar such study). But they wouldn’t have held the same interest for me. I would not feel the same level of personal investment in these topics.

It has really hit me now how much there is in my research topic. Even at confirmation I failed to appreciate the breadth and depth of content involved. Students’ affective domains, constructivism, and mathematics reform, are significant branches of educational literature on their own – combined they become almost overwhelmingly immense. This is when I need to be focused on the ‘end goal’ – what exact point am I trying to make?

My topic is certainly specific enough to be answerable. It passed confirmation last September and I’ve made significant progress in my literature review and data collection since then. I am certain my struggle to keep the focus of my topic sufficiently narrow is not unusual. As with many research students, new literature can bring with it a fresh angle, a different viewpoint to consider. Sometimes these viewpoints are critical and must be incorporated in some way. At all times a consideration of their relevance is necessary: does this particular article need to be included in my literature review?Why? Does the article in question enhance my literature review in some way, or does it serve to be extra ‘padding’ without actually strengthening my argument?

I’m sure there will be countless more times between now and graduation that I question my topic, question my enrolment in a higher-degree research degree, and straight-out question my sanity. But how does one eat an elephant? Why one bite at a time of course! And the same principal applies to undertaking a thesis. Staying focused in ‘the moment.’ Slowly crossing tasks off my (never-ending) to-do list. Writing the monolithic 100k words in pebble-sized fragments of 500. These are the bites in which I’ll devour my elephant.

Posted in More Personal Posts, Research

Tagged college, education, HDR, how to eat an elephant, Masters, PhD, reflections, research, university

Leave a comment